These Two Guys Tried to Rebuild a Cray Supercomputer

And it wasn't easy, even though your iPhone is ten times faster than the machines that used to be model nuclear weapons.

There was a time when the word "supercomputer" inspired the same sort of giddy awe that infuses Superman or Superconducting Supercollider. A supercomputer could leap tall buildings in a single bound and peer into the secrets of the universe.

And chief among this race of almost mythical machines was the Cray. Seymour Cray's first computer, the Cray 1, debuted in 1976, and was the embodiment of all the power that crackled around the supercomputer. It weighed 10,500 pounds. Thirty humans were necessary to help install it. And its first users built nuclear weapons: Model No. 1 went to Los Alamos National Laboratory. Eventually Cray sold 80.

I love this description of its capabilities and style from the National Center for Atmospheric Research (which got Cray's third machine):

With the help of newly designed integrated silicon chips, the Cray-1 boasted more memory (one megabyte) and more speed (80 million computations per second) than any other computer in the world. The Cray’s bold look also set the machine apart. Its orange-and-black tower, curved to maximize cooling, was surrounded by a semicircle of padded seats—dubbed an "inverse conversation pit" by one observer—that hid the computer’s power supplies.

One megabyte of memory! 80 million computations per second! Current smartphones blow away that kind of performance.

But still, there's something to the Cray.

And so, as GigaOm reports, two hobbyists, Chris Fenton and Andras Tantos, decided to try to recreate the machine, but at desktop scale.

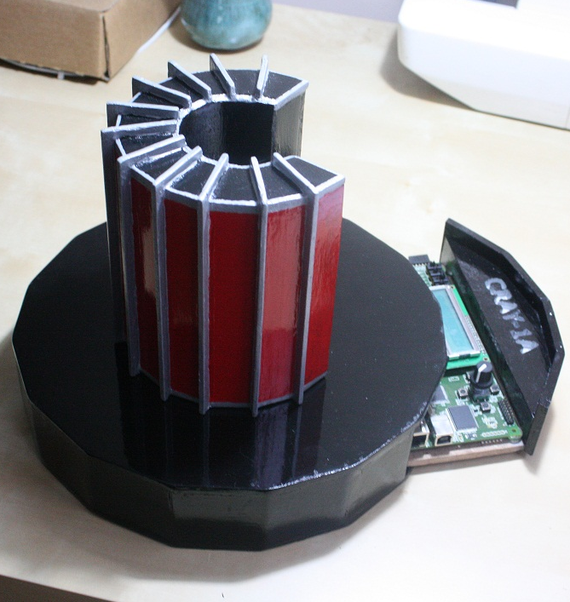

The physical form was relatively easy to put together. They used a CNC machine, painted the wood model, and covered the "semicircle" with pleather. The hardware was easy to get a hold of, too.

"It wasn’t difficult to find a board option that could handle emulating the original Cray computational architecture. Fenton settled on the $225 Spartan 3E-1600, which is tiny enough to fit in a drawer built into the bench," GigaOm writes. "Considering the first Crays cost between $5 and 8 million, that’s a pretty impressive bargain."

The thing that turned out to be tricky, actually, was the software. No one had preserved a copy of the Cray operating system. Not the Computer History Museum. Not the U.S. government. It was just gone.

Fenton searched high and low, eventually finding an old disc pack that contained a later version of the Cray OS. Restoring the software to usable condition proved a ridiculously ornate task, which Tantos, a Microsoft engineer took over. And, after a year of work, they're finally getting somewhere:

[Tantos] rewrote the recovery tools, plus a simulator for the software and supporting equipment like printers, monitors, keyboards and more. For the greater part of the last year, he arduously reverse engineered the OS from the image. Despite a few remaining bugs, the Cray OS now works.

For them and for us, this should serve as a reminder that computing eats its own history. The Cray was the supercomputer, and not a single historian or archivist can show you the working object itself.

Luckily, the world has nerds like Chris Fenton and Andras Tantos. Thanks.

No comments:

Post a Comment